Reinventing landscape management through regenerative pastoral practices

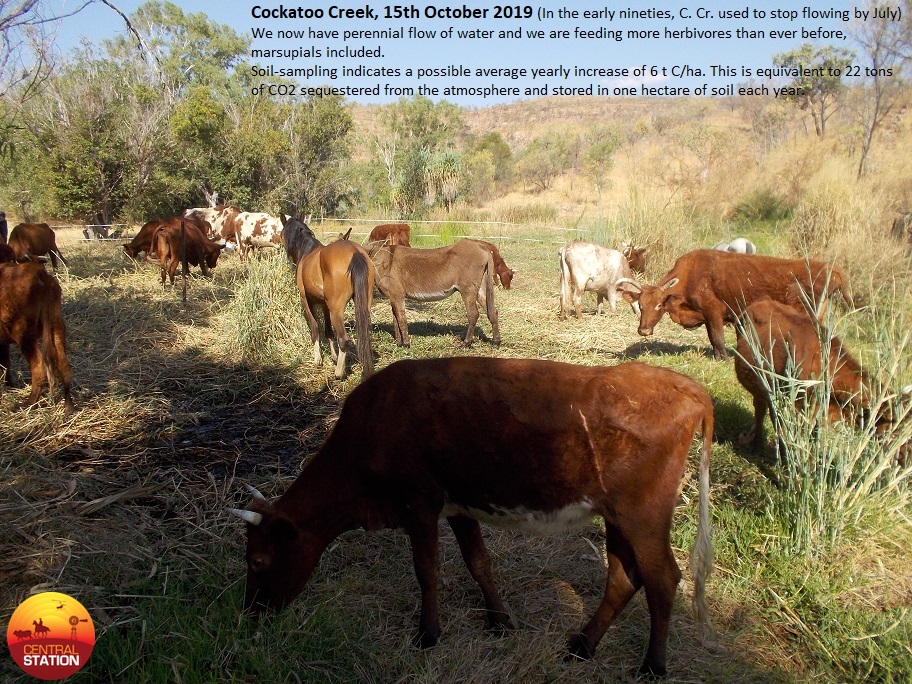

Host: Kachana Station

Written by Chris Henggeler, Owner.

Caveat: Whilst composing this message I remain painfully aware that there are many people doing it really tough all over Australia. When your livelihood is on the line, and everything you own is at stake you do not need others telling you how to prioritise. The landscape vision I share below aims at high targets, but I am a firm believer that aiming high and perhaps occasionally missing, by far outweighs aiming low and hitting. If it were not for those out there who are already collecting runs on the board, now would not be a good time to impart this message.

I’ve heard it said at meetings: People on the land need to be accountable for what they do.

There are people who would readily have us believe that producing cattle is bad for the planet.

Few will disagree that managing land comes with a responsibility. (At least we must all hope that this is the case!) Watching the news this year, I believe that quite possibly the boot may already be on the other foot (at least in Australia): people who wish to exercise the privilege of living in a manner that is seemingly insulated from ecological reality will need to be accountable for their actions and demands.

Early in 2019 I named a folder: “Feral Weather”. This folder is fast filling up with photos and links to news-stories.

Early in 2019 I named a folder: “Feral Weather”. This folder is fast filling up with photos and links to news-stories.

Discussing diet in today’s world has the potential to turn conversations into heated arguments. I wish to stay clear of that one, but for the record, let me take sides with Fred Provenza’s wry observation: “Nobody tells a bacteria or wildlife how to eat, grow and replicate. Even lab rats can self-medicate their own diabetes without our help. Yet the most intelligent species on the planet has to be told by authorities what to eat”. But as Annabelle points out: Pastoralism is about more than food.

The conciliatory message that I wish to impart to my town and city-dwelling cousins is: we are all in this together. Should you wish for those on the land to become land-doctors and better custodians, the choice is actually yours. (To those who really believe that the land would be better without people, I recommend some informative reading: Gardeners of Eden: Rediscovering Our Importance to Nature by Dan Dagget)

There is a saying: Tradition is the ‘democracy of the dead’. (Meaning: Those who are no longer with us, continue to have a say in matters.) Viewed with similar logic, it can be said of the industries and practices that we see around us today, that they are primarily a function of what we could call ‘the democracy of the dollar’. While they may be assisted by political power plays, what actually sustains them is current flow of cash.

Everybody who spends is actually casting votes with every transaction they make. As a result, (whether we clock up debts or not) collectively we all get what is being paid for on a daily basis.

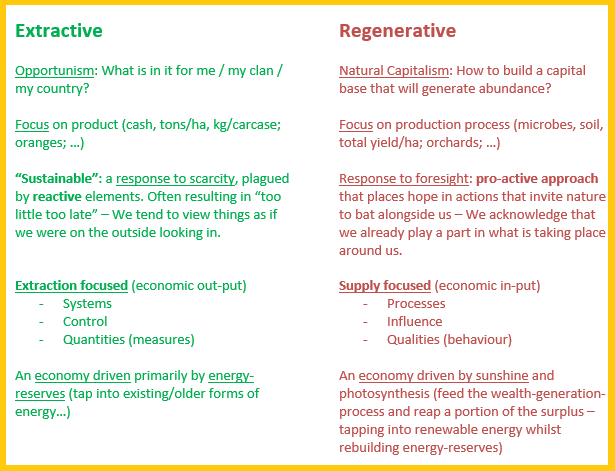

Those who have experienced being in a vehicle when the driver has taken a wrong turn in traffic, will appreciate that an immediate U-turn is seldom the best response. First, we need to identify that there may be a better way than the road we now find ourselves on; then we begin to explore options. Similar challenges are now faced by consumers as well as by industry-players being confronted by a regenerative paradigm.

My introduction to the word “paradigm” came in February 1997 when Terry McCosker taught at the first Grazing for Profit School in the Kimberley. Classroom-learning was never something that did much for me, so Terry might not have been the only teacher disappointed in what I took home.

But I did take home a new word and a new understanding of what a ‘new grazing paradigm’ might mean for northern Australia. Is there a better trajectory than the one we are on?

We had taken on a 750mm-rainfall desert. Without productivity, there would never be production. As a wannabe producer, with enough cattle to eat, but not enough animals to sell, what was there to risk? Credibility of course, but people were thinking that we were crazy to be out here to begin with.

Were our herbivores actually worth more to us (and to the downstream community) living and working as land management tools, than dying young? That turned out to be a question that persists even now. At producer-levels this translates to: Is there a commercial justification for working-animals as well as for breeders and/or sale animals?

With exploration, the learning began. Allan Savory’s school of thinking supported the importance of how large herbivores behave (i.e. function) in a landscape. Christine Jones informed us that in Australia “sustainability was not a worth-while option”, we do not wish to sustain degraded environments, we need to “aim for regeneration”. Christine also informed us that “set stocking equated to zero grazing management”. Then RCS brought to Australia Arden Anderson, Elaine Ingham, Johann Zietzman and others. Members of our Land Conservation District Committee (LCDC) sent a representative to listen in and to report back. For Kimberley managers there was much new information to process. It included hearing about relationships in the soils that could not even be seen! It was the beginning of a new era. Instead of a ‘millennium bug’, we in the bush were given the internet.

Talk about paradigm-overload. So many new and good ideas! Many time-wasters too…

Land managers and operators on different continents were comparing notes. But what was relevant to Northern Australia? This proved to be the wrong question.

Each property remains unique. Each business has unique aspirations as well as a unique set of constraints. Each manager has uniqueness, and then there is the season, the people and of course the politics. While we could inform each other about successes, mistakes and pitfalls, each of us still had to glean what was relevant to her/his context.

As practical people on the land often do, they get on with the job at hand. They watch, they listen, and when it appears to make sense for them to do so, they change things. Anybody who was expecting spectacular ‘U-turns’ would have been disappointed. Players have come and gone, management and leases have changed hands, yet the pastoral industry in the Kimberley is still here. It has survived two world-wars and associated economic challenges, it survived the closure of meat-works and if it ever came to the termination of live-export, my bet is that it would survive that too.

Why?

Australia lacks water-security and not only are pastoralists in the driver’s seat, they are better equipped than ever before!

My observation over the last 40 years in this country has been that Australia’s greatest biosecurity risk is ‘desertification’. i.e. the actual loss of life in and on our soils, is itself is a threat to life and to livelihoods in general.

Regenerative pastoral practices have the potential to deliver water-security at landscape levels.

Water security addresses a three-part challenge: drought-mitigation, flood-mitigation and the mitigation of the effects of fire. Abundant access to surface water then literally becomes a natural flow-on effect!

Players in the industry are already testing and making effective use of new tools, new knowledge and new skill-sets associated with regenerative practices. These include a range of low-tech high-skill options based on bio-mimicry. Newcomers to the land have access to this learning as well.

Right now, I see no serious incentives to tackle the broad-scale rehydration of landscapes. However, it appears that industry-players are ready to respond when the financial cues do appear. (This applies even to those in the industry who are not watching this space at the moment!)

According to some scientists Australia has already run the experiment of replacing herbivores with fire. This supposedly happened many thousands of years ago.

Can our economy afford a re-run? Watching the news makes me think the answer is a resounding ‘NO’.

Why then do we allow so much biomass to be incinerated each year?

Increasingly people are asking the same question.

However once incentivised, we as an industry will be in a position to step up to the challenge. We have Australia’s New Megafauna at hand with many other new Australians (people, animals, plants and microbes) to choose from.

These are exciting times in rural Australia for people who are young and energetic with a good attitude, and who are willing to invest in their skill-set accordingly.

It is probable that there will always be contractors earning money by putting to use big machinery to build dams and clear fence lines.

What about using cull-animals or what we now call feral animals to improve rainfall-infiltration and pasture-improvement in a back paddock?

In better country, what about using weaners or store animals for the same process and then getting a percentage of the weight-gain as a contract-incentive?

What about weed control and erosion control in national parks?

Should we not be using animal-energy to fire-proof communities? (People in other countries are already doing this sort of stuff for reasons of their own.)

I’ve read about drovers purchasing stations. I know truckies and machinery contractors who later bought pastoral leases. I hope I live to see a new generation of locally bred, self-taught land-doctors earning their livelihoods with ‘working herds’ that appreciate in size, quality and value as landscapes are rehydrated and new levels of productivity are achieved.

Some of what I have seen happen around me in the last thirty odd years scares me, but there is also scope for hope. Each of us has the choice to contribute to better outcomes.

In summary: There is a call for ecological restoration in many seasonally dry regions in the world. Becoming land-doctors is actually about ‘rainfall management’. All the relevant skills already exist within the pastoral industry. They can be learned, taught, improved on and combined to suit a particular context.

It is the Behaviour of Australia’s NEW MEGAFAUNA that is the most powerful tool at our disposal. This tool (if managed accordingly) will run on sunshine.

Many pastoral players in Australia already excel in what they do. Such people are now beginning to open up new self-employment opportunities and new jobs on the land.

May the season be kind to all land-managers who are doing it tough this year and may we end up with a regenerative tsunami that offers opportunity and hope to those who feel a calling to live in line with how our landscapes function.