The wet season that never came

Written by Steph Coombes, Central Station editor

Drought isn’t a new concept to Australian farmers. Much of the east coast has been in drought for the last 7 years, or even longer.

However, over here in northern WA we’ve been pretty bloody lucky. There’s been a few dry times, but nothing as prolonged and gut wrenching as what we’ve seen our eastern cousins go through.

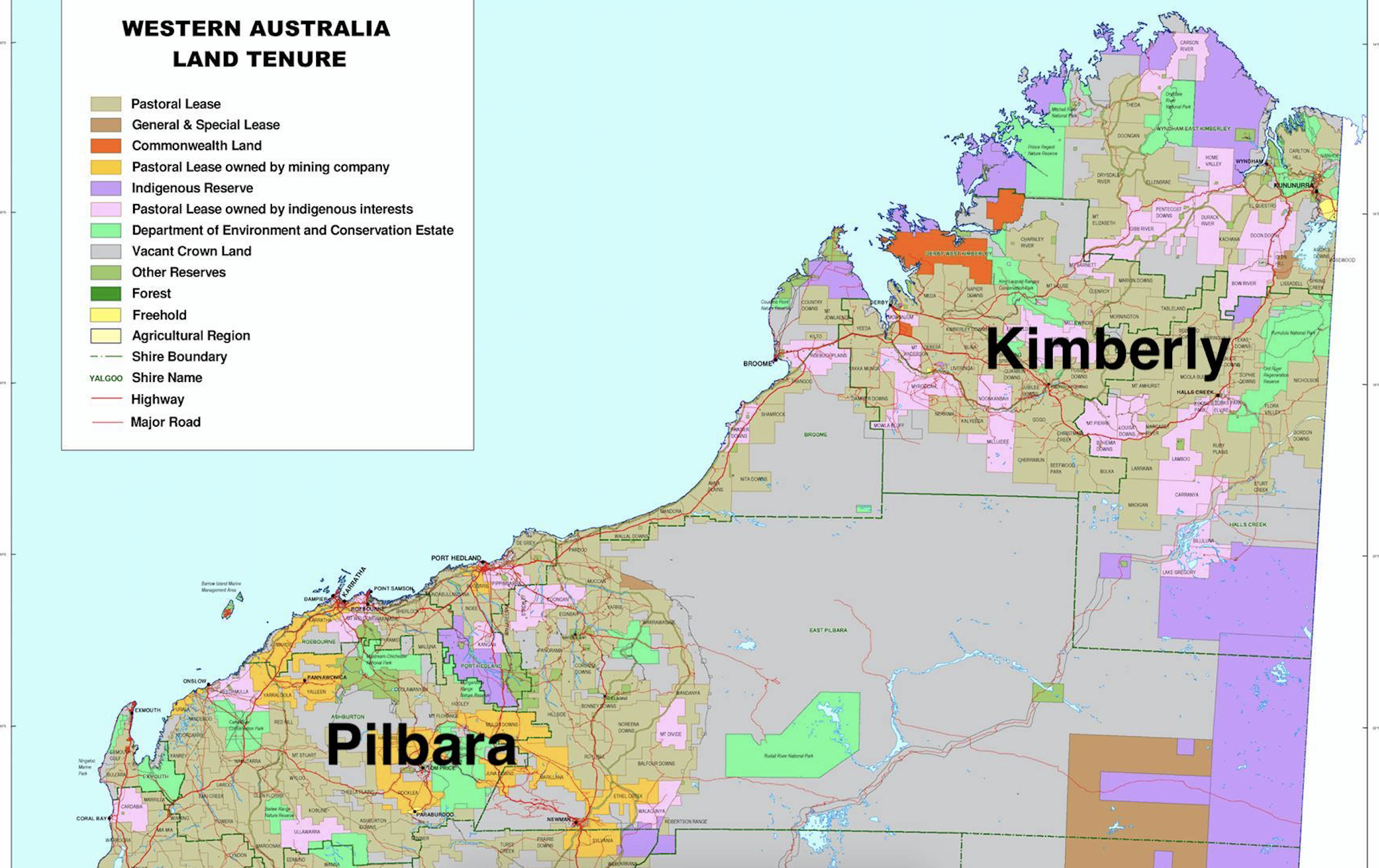

The Pilbara and Kimberley regions aren’t immune to a lack of rain though, and that’s exactly what these two regions experienced during the most recent wet season (2018/19).

The Pilbara and Kimberley cover approximately 1,000,000 km2, or 40%, of Western Australia’s land mass. There are approximately 150 pastoral leases running an estimated 900,000 head of cattle; about 1/3rd of those in the Pilbara, and 2/3rds in the Kimberley.

The Kimberley has most of the largest pastoral stations and herd sizes in Western Australia due to its relatively reliable rainfall and sustainable native pasture base. It has what we call a tropical monsoon climate – there is a defined wet and dry season.

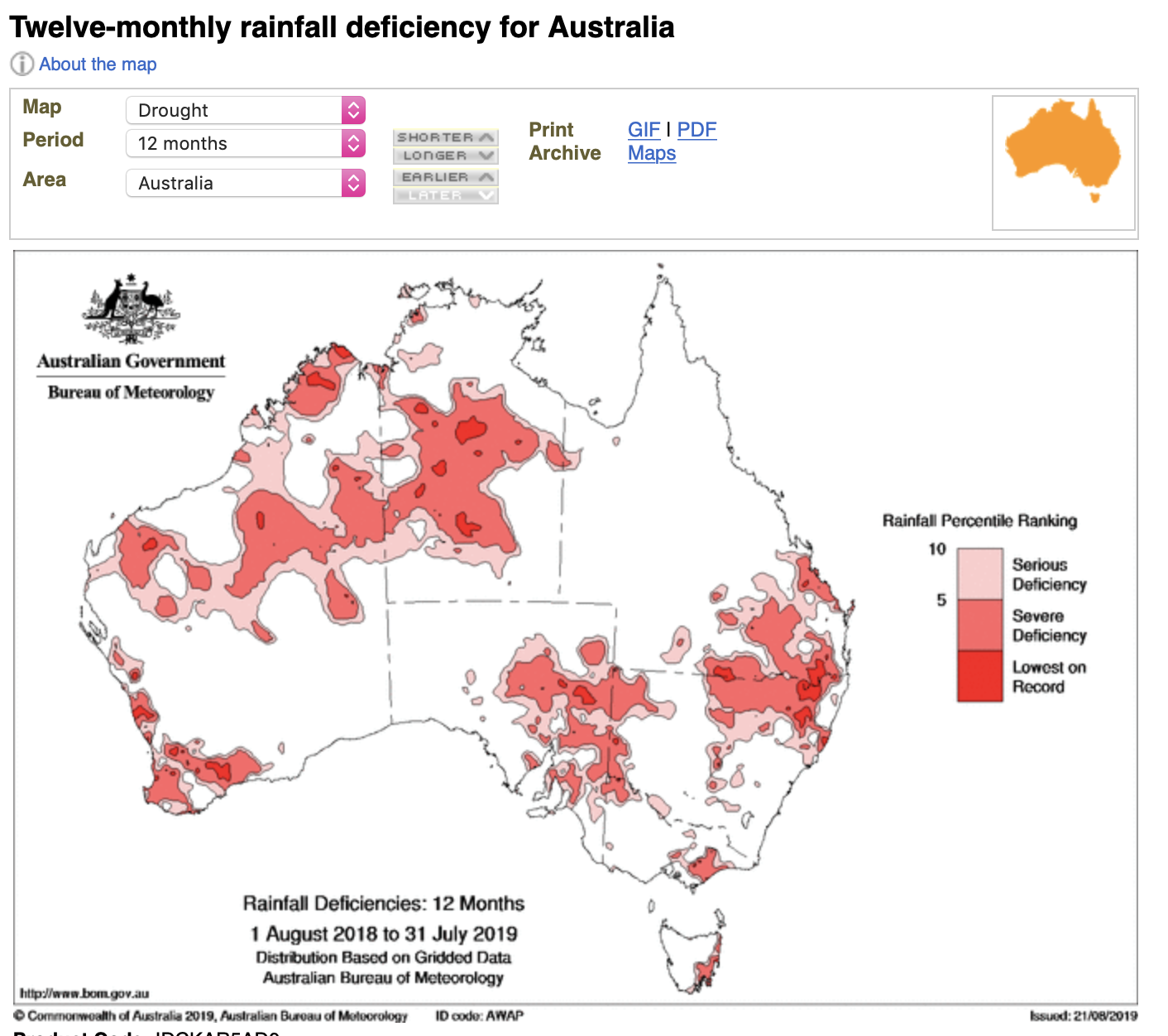

In comparison, the Pilbara consists of large areas of shrub lands, and receives both summer and winter rainfall, though neither is reliable. It also receives less rain (see the decile map below), as it is what we call a semi-arid climate. This is why there are less cattle in the Pilbara – they need to have a more conservative stocking rate than the Kimberley.

They are two different environments, but they both received below average rainfall and above average temperatures this past wet season. This meant that there was extra pressure on the rangelands, livestock, water infrastructure, and of course on the people who worked tirelessly to monitor and manage all of the above.

I should note that there were a few properties which received late rain from Tropical Cyclone’s Veronica and Wallace. (Veronica also caused significant infrastructure damage and livestock deaths, but the impacts were fairly contained compared to the widespread devastation we saw in Queensland earlier this year.) However, the majority of pastoralists in the Pilbara and Kimberley have been faced with a challenging season for 2019.

Pastoralists wear many hats, and I’m not just talking about all the ones they get given from stock agents, supplement companies, transport companies, local events etc. (honestly, I’ve never met a group of people who own so many caps!)

Managing a pastoral lease is an insanely complex job. You’ve got to manage the landscape, livestock, infrastructure, people, the business, and of course your personal life. A pastoralist can go from pregnancy testing cattle one day, to sinking a bore the next, to preparing a BAS tax statement the next, and training and counselling staff the next – at any one time there’s a lot of balls in the air and it’s bloody full on.

But, at their core, pastoralists are stewards of the land. They use livestock to manage the landscape and make a living. I don’t know a single pastoralist who isn’t striving to leave the landscape in a better condition than it was when they assumed management.

So, when the rain doesn’t come, and the pressure is building, how do these men and women take on the challenge?

Well, the first thing to note is that many pastoralists plan and prepare for dry times, otherwise known as managing for climate variability.

When looking at historical data, rainfall in Australia is more variable than anywhere else in the world – more often than not, many places do not actually receive their “average” annual rainfall. This is especially true for northern Australia – and in fact the Kimberley has received higher average rainfall in the last 25 years when compared to the average over the past century. That means, what is considered a “normal” rainfall for most people’s living memories, is actually higher than normal – which may have resulted in higher expectations from the current generation. There’s a bit of chatter around at the moment that annual rainfall totals may start to decline and go back to more “normal” figures.

So, whichever way you look at it, pastoralists are challenged with managing their natural resources in a highly dynamic and unpredictable climate. Luckily, there’s a few management interventions available to avoid ending up with no feed, no ground cover, and damage to the rangelands.

Tools for managing climate variability include:

- Climate data (short and long term forecasts, climate drivers)

- Determine and use seasonal decision dates

- Evaluating stocking rates vs carrying capacity

- Supplementation (not supplementary feeding)

- Have a plan to reduce pressure on your country (agistment or destocking)

In this blog, I’m going to talk about the second point – using seasonal decision dates.

Seasonal decision dates are trigger points which require the pastoralist to assess the situation and enact a pre-determined management strategy.

Decision dates are related to the growing season. So, what is this growing season I speak of?

The growing season commences at the green date. The green date is when there has been enough rainfall, resulting in sufficient soil moisture, and the temperature is high enough, to initiate and sustain growth. The key word being “sustain”. Sometimes you’ll get a big storm at the start of the wet and then nothing for weeks. This isn’t the green date, it’s a false start.

The growing season is the active phase of plant growth. Plants are alive all year round, but they don’t grow all year round. Most plants are dormant in the dry season. The end of the growing season is indicated by a drop in soil moisture (via cessation of rain) and in some regions, a drop in temperatures that is sufficient to slow or stop pasture growth.

So, we’ve got the start and the end of the growing season down pat, agreed? Next is the production point. The production point is when there is enough quantity and quality of pasture to sustain weight gains of stock. It usually occurs between three to six weeks after the green date. It doesn’t rain grass, so we need to wait long enough for sufficient quantity of new growth that stock can access enough to fill their rumens with high quality pasture and enable weight gains.

We need to know when the production point is when doing a forage budget. Just like we all budget time and money, pastoralists have to budget their grass. They need to know how much they have, and how long it will last – which of course depends on how many mouths they are feeding and how much rain they’ve had. With a lack of rain comes a lack of pasture growth. It’s not just the quantity of pasture though, but also the quality.

When preparing a forage budget, the timeline should run from the end of the growing season to the next production point. Once the pasture is at its maximum quantity, at the end of the growing season, pastoralists need to budget until the next growing season when there is sufficient quantity and quality of pasture to sustain weight gains of livestock (aka the production point). Thinking you only need to budget until the start of the wet season is an easy mistake to make – “We just need to make this grass last until we get some rain” – but remember, it takes the right combination of rain and temperature to sustain pasture growth, so you need to make your grass last until there’s enough to start all over again.

The 3 Decision Dates (D-Days).

- D-Day #1 – the midpoint between the start and end of the growing season.

If there hasn’t been a start to the growing season by halfway through the usual growing season, then it’s highly unlikely that we’ll get the rain and pasture growth needed to meet the average/median annual pasture growth by the end of the season. For example, if the middle of the growing season is 15thFebruary and you haven’t received a reasonable start to the growing season by then it’s a pretty risky bet to hedge that you’re going to get average pasture growth by the end of the growing season. This is the first trigger point for pastoralists to assess what’s going on and start enacting a plan.

- D-Day #2 – the end of the growing season

This one makes senses. Once the growing season has finished, there’s no more guessing about extra rain and growth you might get. Once it’s done, it’s done and you know exactly what you have to work with. This is the time to do a forage budget, to work out how many cattle that grass can carry until the production point.

- D-Day #3 – the middle of the dry season

The last date is in the middle of the dry season, and is a “checks and balances” measure. It’s important to check in and see if we’re on track and meeting our forage budget, or under/overgrazing. Hopefully if all is going well, the supply will be equaling demand, but if the numbers come back that you don’t have as much grass as you thought you would have, then it gives you firm data to be able to make a decision about reducing numbers in affected areas, either through shifting cattle, agistment or destocking.

Really, a lot of it comes down to planning. As Col Paton, a lead deliverer of the MLA Grazing Fundamentals and Grazing Land Management course says:

“Regardless of weather forecasts, make sure:

- Your land is always ‘rain ready’ (good land condition and attached ground cover)

- You regularly monitor pasture, animal and land condition so that you can anticipate and avoid: feed shortages, diminished animal performance and land condition decline

- There is flexibility in your herd structure and grazing management to allow for timely adjustment of stock numbers”

Want to know more? Attend a Grazing Fundamentals EDGE workshop!

Grazing Fundamentals EDGE is a one-day workshop designed to give you a broad understanding of the components of the grazing production systems and the core, scientifically-backed principles behind optimising grazing land productivity.

Participants will be able to make better decisions to achieve grazing performance by looking at the local influences on pasture yield and quality and how seasonal planning and strategic management can be used to achieve land condition and animal production goals.

Attending this workshop will help you to:

- better understand the connection between land condition, pasture growth and animal production

- understand how climate influences pasture growth

- allow for climate variability when planning livestock management

- build a seasonal climate profile for your location.

What you will learn:

- environmental regulators of pasture growth and quality

- local seasonal pasture growth patterns and key decision dates

- how soil properties influence pasture growth

- how grazing affects pasture plants, their productivity and growth

- how to assess land condition and how this impacts on carrying capacity

- when and how to use pasture spelling

- principles behind successful grazing systems

- what’s involved with forage budgeting.