Just keep breedin’ (The story behind our parody video)

Written by Steph Coombes, Central Station editor

If you’re reading this, chances are that you’ve seen a parody video called “Breedin’” set to the song “Breathin’” by pop princess Ariana Grande. If not, hold your horses, and watch the video first by clicking here.

The song, sung from a cow’s point of view, makes mention of: early weaning, segregation, supplementation, body condition score, pregnancy testing, cycling and anoetrus.

So, what does all of this mean, and why do we care about it so much?

Reproduction is probably the single most important factor affecting the economics and profitability of beef cattle breeding operations in northern Australia. For bulls, reproduction is about the capacity and ability to sire a large number of viable offspring each mating year. For cows, reproduction is all about the capacity to conceive and rear a calf to weaning each year following puberty (yep, cows have to deal with puberty too, and the ladies have to do a lot more work than the men!).

The cow that produces a live, normal, calf within 365-day calving intervals and rears that calf to weaning is superior to the cow that has longer inter-calving intervals or fails to wean her calf.

Inter-calving what? Ok, let’s back up a minute and touch base on the bovine reproduction cycle 101!

Bovine reproduction cycle 101

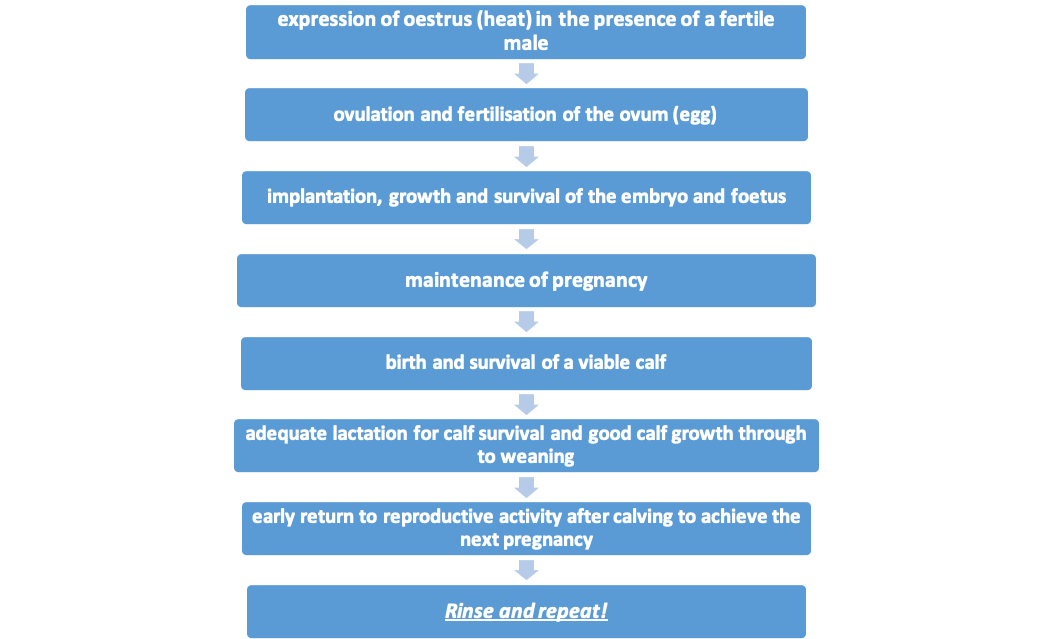

Reproductive events in the female cattle are shown in the diagram below.

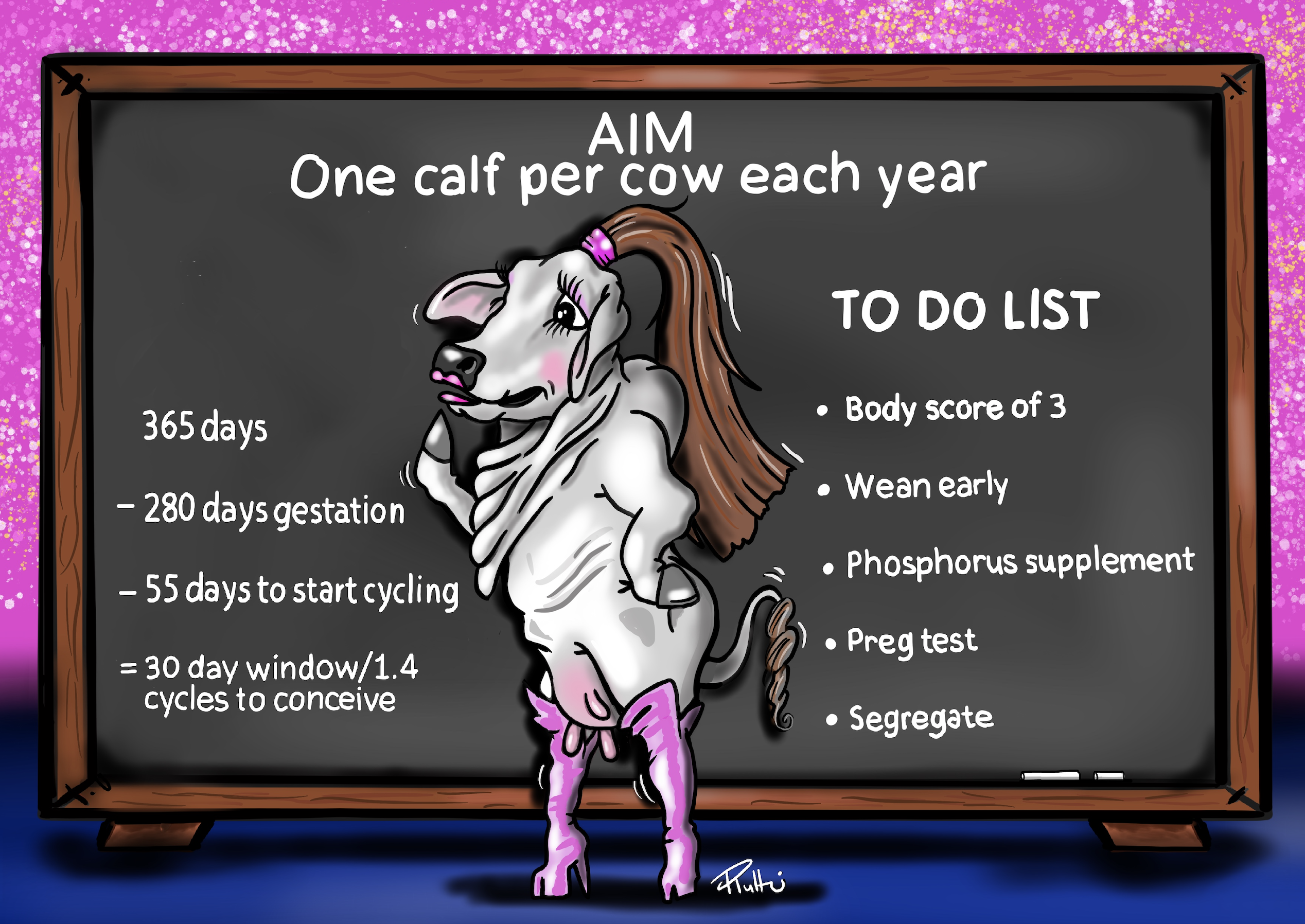

The aim is to get one calf per cow each year.

Why? There’s 365 days in each year. The average gestation period for cattle is 280 days.

(365 days in a year) – (280 days gestation) = (85 days to get the cow back in calf).

85 days to get back in calf – too easy! …

Except, it’s actually quite difficult…

Female cattle cycle approximately every 21 days. So:

(85 days to get back in calf)/(21 day cycle)= 4.04 chances to get the cow back in calf

if she were to have a calf each year.

Jeez, if third time is a charm, surely 4 chances will have us laughing, right?

Nope.

“Calving to first heat interval” & “post-partum anoestrus” – the rain on your parade.

Cows don’t start cycling (the onset of oestrus) as soon as they’ve given birth. The period of time between a cow giving birth and when she first cycles again (aka when she’s first able to get pregnant again) is called the “calving to first heat interval”.

Now, the reproductive tract and ovaries of a cow “should” return to normal and reproductive cycles “should” recommence about 35-40 days post-calving. You’ll notice I’ve used inverted commas around “should”. That’s because in many northern herds this period is prolonged; some cows do not recommence cyclic activity for up to 7 months after calving. In some breeds it is even longer … sister is taking a holidayyyy!

On average it takes a minimum for 55 days for a cow to return to cycling after calving. The condition is known as “post-partum anoestrus” (PPA) aka “ovarian inactivity”, and it is a major factor influencing the level of fertility in many northern herds.

So, lets revisit the maths:

(85 days to get back in calf)-(55 calving to first heat interval) = 30 days to get back in calf

(30 days to get back in calf)/(21 day cycle) = 1.3 chances to get back in calf

It’s not a very big window, is it?

Controlled mating – the one time its socially acceptable to be a control freak

In an ideal world, cows would be control mated. That means they’d only be allowed to socialise with the bulls for a set period of time, say 8-12 weeks, and then after that it would be like being sent to an all-girls boarding school… not a boy in sight. As a result, all the cows would have their calves in the same 8-12-week time period.

Why do we want all the calves to be born around the same time?

Up north, the available nutrition from pastures varies depending on the time of year. The quality is highest over the wet season when the pasture is actively growing, and then it rapidly declines over the dry season as the plants become dormant. (This varies slightly from region to region).

The aim of the game is to match the time of calving to when the available nutrition is at its highest. Let me explain why…

The energy required by a cow to maintain the lifestyle to which she is accustomed (aka being alive with normal bodily functions) is called “maintenance energy”. Her energy requirements increase throughout her pregnancy as she grows her calf (foetal development) and begins to produce milk, with the peak energy requirements being around the time of calving.

Once the cow has given birth to the calf, she needs even more energy to maintain her lifestyle (aka normal bodily functions), produce milk so her calf can grow, and recommence reproductive activities. Like, a lot more energy.

So, the aim is to match the cow’s peak energy demands with when the maximum nutrition is available.

But, remember how I said “in an ideal world…”?

Well, not many people up north use controlled mating, and that’s because of a number of different barriers. Here’s a few examples:

- Some people don’t have the infrastructure (fencing) to separate their cows and bulls. “Well, just build a fence” I hear you say. Yeah, so, fencing is kind of crazy expensive. And when you manage several hundred thousand acres, just image how much fence you would need… Fencing is generally done bit by bit as properties can afford it.

- Some people can’t access their property at the times of year they would need to pull out and put in their bulls, due to wet season flooding.

- Some people have feral cattle on their property, or on neighbouring country (whether it be the neighbours, national park, crown land etc). So, even if they did pull out their own bulls, there’s a good chance the feral bulls would mate with their cattle. So, what do you do? Give the feral bulls a free run at your ladies, or leave your good bulls in there so you at least have a chance of getting better quality calves?

For the most part, many stations have year-round mating, i.e. the bulls party with the cows all year round. As such, cows can get pregnant any time of the year, and calve any time of the year … including “out of season”, when the available nutrition is really poor.

What happens when a cow has a calf out of season? To cut a long story short, the calf starts to suck the life out of her (sounds dramatic, but the consequences can be quite dramatic on herd productivity and profitability). The cow simply cannot access sufficient energy from the pasture to be able to meet her energy demands to raise that calf.

Like most human mums, cows tend to look after everyone else first, even when it’s to their own detriment. A cow will put all their energy into producing milk for their calf/weaner, at the expense of her own condition – i.e. instead of using energy to look after herself, she’ll start to lose weight.

When a cow loses body condition, her chances of getting back in calf are significantly reduced, let alone her chances of getting back in calf within that tight timeframe to have a calf every year. Plus, when they have a calf out of season the whole reproductive timeline gets out of sync, and thus the cycle of poor reproductive performance begins and money starts walking out the front gate…

So just think about it – if you want a calf every year, basically, once the cow has birthed calf #1, she needs good enough nutrition to have energy to a) stay alive, b) produce milk for calf #1, and c) start cycling again so she can fall pregnant with calf #2, while still raising calf #1.

To have one calf every 365 days, a cow needs to fall pregnant within 4 months of calving, also known as “P4M” in the CashCow report.

So, what are our options?

- Prevent heifers and cows from lactating in the dry season by control mating

- Manage heifers and cows which are lactating in the dry season (i.e. out-of-season calvers)

If controlled mating isn’t an option, then the best bet is to actively manage the cows you know which are going to calve outside of that peak nutritional availability.

Segregation – providing specialised care for mums-to-be

Segregation is the act of setting different things apart for management purposes, i.e. drafting cows into separate groups so you can manage them differently.

As I mentioned before, when cattle are mated all year round, they can calve all year round. The cows that calve outside of the peak available nutrition are what we consider “high maintenance”. We all know someone who is a little high maintenance … #AmIRight? These are the cows that are prime targets for losing body condition because they just won’t be able to consume enough feed to meet their energy demands as they give birth and raise their calf.

Now these ladies who calve at the “right” time, they’re as low key as can be. No worries. They’re like that friend that drinks the tap water and definitely believe in the 10 second rule when food has been dropped on the floor, just cruisey as. These out-of-season calvers on the other hand, they’re more like your friends who demand refrigerated, filtered, bottled water… #highmaintenance.

So (remembering that this is a very brief/crude overview of the topic) the gist of it is that we can segregate breeders by time of calving and target supplement the high maintenance groups. The ladies who are going to calve out of season need a helping hand, a little extra TLC.

To be able to segregate cattle by time of calving though, we need to know if a) they are pregnant, and b) when they are expected to calve. This knowledge can only be found through pregnancy testing. There’s a few different options for this including manual palpation (getting elbow deep in a cow’s backside) and ultrasound.

Before I go on, I should mention that one option is that you could not segregate your cattle, and just provide supplement to all of them, but providing supplement to cows who don’t need it is just a waste of money – and any profit to be made in this industry comes from your margins, so ain’t nobody got time for that!

Body condition score – judging a cow by her (fat) cover

The body condition score of the cow at calving is the single most important factoring affecting her ability to get back in calf after calving. A breeder needs to be in a body condition score of 3 or better, on a scale of 1-5, at calving in order to have the best possible chance of conceiving again within 85 days of calving.

It’s about setting that cow up for what’s to come. After calving she’s going to be working hard feeding her calf, and likely to drop a bit of weight. The better condition she starts off in, the better she’ll end up in.

To give cows the best chance of maintaining their body condition, we need to set them up to calve at the right time of year. For those rebels who are going to calve out of season, a dry season supplement can give them a helping hand.

Early weaning – give a girl a break!

When a cow calves out of season, she’s already got an uphill battle ahead of her. She has to try and raise a calf to weaning at a time when there’s bugger-all nutrition around. If left to do this, there’s bugger all chance she’s going to start cycling and reconceive again in the timeframe you want.

Early weaning – removing the calf at a young age – gives these girls a reprieve from the energy demands of raising a calf out of season. It’s commonly confused as being a practice to help a cow get back in calf with the next calf, but it’s actually to help her get in calf with the calf after that.

Wait, what?

When you wean calf #1, the cow should already be pregnant with calf #2. Remember, we want cows with a calf at foot and one on the way if they’re to have a calf every year (*cue Loretta Lyn here*). Early weaning calf #1, helps keep the cow in good condition going into birthing out calf #2, which sets her up for her best chance of conceiving calf #3.

It’s a long game, and you may not see some of the benefits from the decisions you make today until 2-3 years down the track.

Phosphorus – not just for your paddocks

“Northern Australia is severely phosphorus deficient” said every person ever. But, it’s true, and it can have a massive impact on breeders.

Phosphorus is one of the top three limiting nutrients, right after energy and protein – so, even if a cow has sufficient levels of every other nutrient, if she ain’t got enough phosphorus, no deal.

Phosphorus affects feed intake. If a cow doesn’t have enough phosphorus, her feed intake will be restricted. I know what you’re thinking, and I’ve thought it too, “How can I make myself phosphorus deficient, so I stop snacking every 5 minutes?”. Anyway, back to the cows.

Now, pastures become deficient in phosphorus during the wet season – the time of year where the grass is lush and green, full of protein and energy and people could be forgiven for thinking that their cattle don’t need to be supplemented. What can happen though, is that there’s all this gorgeous feed around, but the cows aren’t able to eat as much as they should.

The mob out of the Northern Territory DPIR have done some wild research into this in the past few years and there are massive gains to be made from supplementing with phosphorus. Before you pick up the phone and start ordering bulka bags of phosphorus though, there’s also other research and economic modelling which shows it’s only cost effective if your mob are acutely deficient, not moderately deficient. It’s a decision that requires a bit of thought, and a few conversations with your consultant or local extension officer.

Ok, I’ll stop now.

So there you have it, a very brief introduction to the reproductive challenges faced by cattle and cattlemen alike in northern Australia!

To learn more:

- Visit FutureBeef.com.au

- Enroll in a MLA Breeding EDGE course

- Download “Managing The Breeder Herd – Practical Steps To Breeding Livestock In Northern Australia”

- Download “Heifer Management in Northern Beef Herds 2nd Edition”